FORUM-ASIA organised its first Global Advocacy Learning Programme (GALP) on Human Rights and Development in Thailand on 19-25 November 2017. Prior to the event, participants were asked to submit case studies on specific issues related to human rights or development, with a particular focus on the role played by civil society organisations in addressing the issues. For more information on this year’s GALP, click here. Below is a case study written by one of the participants of the GALP in 2017.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of FORUM-ASIA. Assumptions or recommendations made based on the analysis in the article, should also be accredited to the author, and do not always align with policies or positions of FORUM-ASIA.

Case study: Glooming effects of Enforced Disappearances in Bangladesh

Consequences and challenges for human rights defenders and the families of the disappeared

by Md. Ashiqur Rahman

This case study focuses on the consequences of enforced disappearances as well as challenges for human rights defenders and the families of the disappeared in Bangladesh. There are several incidents of enforced disappearance taking place across the country, indicating the deterioration of law and order. Despite the growing number of incidents, and allegations of involvement of law enforcing agencies, the Government has not taken any concrete action against perpetrators. Moreover, the Government is not allowing any civil society organisation (CSO) to conduct activities and campaigns against enforced disappearance.

‘Enforced disappearance’ is a particularly heinous violation of human rights and a crime against international law. It affects victims in many different ways, including a feeling of constant fear for their lives. Their families go through an emotional rollercoaster of hope and despair. They constantly wait for happy news that never comes. The disappeared person is removed from the protection of the law.

Article 2 of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED)[1], defines the term ‘enforced disappearance’ as:

- ‘The arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty;

- By agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State;

- Followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person;

- Which places such a person outside the protection of the law.’

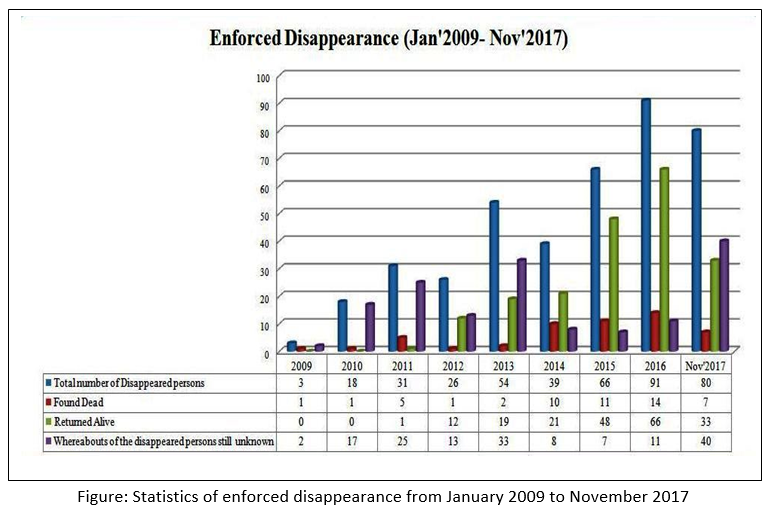

According to information gathered by Odhikar[2] from January 2009 to November 2017, 408 people were allegedly ‘disappeared’. Among them, 152 were allegedly disappeared by the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), 50 by the Police, 107 by the Detective Branch (DB) of the Police, 11 jointly by RAB and DB police, and 88 by other law enforcers. Among them, 52 people were found dead after being disappeared. According to Odhikar’s documentation, in some cases, law enforcement agencies arranged press conferences and introduced the disappeared persons as arrested in different charges like vandalizing vehicles, bomb blasts, involvement in a conspiracy against the state, extremism etc. Sometimes, the victim families got to know from different sources that their family members were in jail. Though they were disappeared a long time ago.

The crime of enforced disappearance has persisted under various regimes due to autocratic political systems, including civil and military dictatorships, which suppress self-determination and peoples’ movements. However, in Bangladesh the context is different. Currently, enforced or involuntary disappearances are taking place to silence dissenting people and opposing political groups. These crimes are committed to clear the table for the ruling party or to settle past and existing animosities towards specific people or groups. Due to their involvement with opposition political groups, different people in Bangladesh became victims of enforced disappearances.[3] Thus, the acts of enforced disappearance have become an institutionalised practice of repression resorted to by the Government. Moreover, the incidents of enforced or involuntary disappearances often ended up in extrajudicial killings.[4]

Enforced disappearances re-emerged[5] in Bangladesh in 2009, and since then occurrences of this crime have massively increased.[6] These enforced disappearances are taking place with the full knowledge and implicit approval of the Government. According to both Odhikar’s findings, press conferences of the families of the victims, and published news in various print and electronic media, the majority of the reported enforced disappearance cases follows a specific pattern. First, members of law enforcement agencies arbitrarily detain, abduct, or cause individuals to disappear from various places in broad daylight, mostly without any arrest warrant. In many cases, these arbitrary detentions occur in victims’ homes in front of family members. The agents who carry out these abductions wear uniforms or plain clothes and drive vehicles typically used by law enforcement agents. In some cases, law enforcement agencies deny the arrest. Days later the arrested persons are produced before the public by the police or law enforcement agents, or handed over to a police station to appear in Court later. Or their dead bodies are found. In many cases, families of the disappeared, witnesses, and the victims who return to their families claim that law enforcement agencies initially picked up the victims.

The Government is using law enforcement agencies to suppress political opponents, allowing members of such security forces to enjoy impunity. As a result, they carry out various human rights violations, including enforced disappearances.

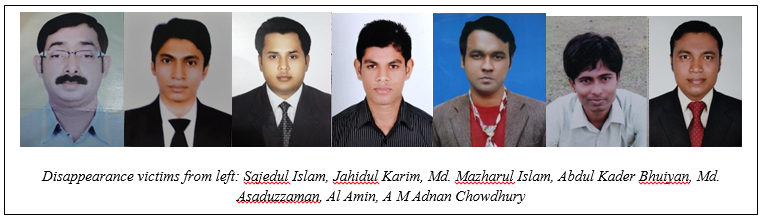

On 4 December 2013, Sajedul Islam Sumon along with Russel, Masum, Al-Amin, Rana, and Tanvir were gathered in the house of Tanvir at block no. I, Bashundhara area, Dhaka. The house was under construction at that time. At around 8:00 p.m., Rasel, Rana, Masum, and Al-Amin left the place to go to their homes. A few RAB members wearing uniforms stopped them and took them into a microbus. Later they were taken back to the house and a worker was asked to identify Sumon and Tanveer. Upon identification, they were taken away again by the RAB

Eyewitnesses confirmed that around 8.30 p.m. they had seen three vehicles and one microbus with RAB-1 written on it arrive and that some RAB members with arms had picked, as recounted by Sajedul Islam Sumon’s mother.

Later on, relatives went to Bhatara Police Station, Gulshan Police Station, Tejgaon Police Station, Uttara Police Station, Detective Branch of Police, RAB-1 office, RAB-2 office, and other places in search of the missing people. But no one in the places they went gave any information regarding their whereabouts. When one of the victims’ relatives went to file a General Diary (GD), the police station authority told him that he could not file a GD if he mentioned RAB. Later, the victim’s family filed a GD saying that the victims could not be found. Until today their whereabouts are unknown.

According to Article 6.1 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), every human being has the inherent right to life. This right is protected by law. No one should be arbitrarily deprived of his or her life. Article 3 of the ICPPED, states that each State Party shall take appropriate measures to investigate acts defined in Article 2 committed by persons or groups of persons acting without the authorisation, support, or acquiescence of the State, and to bring those responsible to justice. Article 4 continues that each State Party shall take the necessary measures to ensure that enforced disappearance constitutes an offence under its criminal law. As of now, 97 countries have signed the ICPPED, but Bangladesh has not done so yet.

Such incidents of enforced disappearance also violate Article 9[7] and 16[8] of ICCPR and Articles 31[9] and 32[10] of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. According to Article 33 of the Constitution ‘no person who is arrested shall be detained in custody without being informed, as soon as may be of the grounds for such arrest, nor shall he be denied the right to consult and be defended by a legal practitioner of his choice…)’.

The 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which came into force on 1 July 2002, considers enforced disappearance a ‘crime against humanity’.[11] Bangladesh ratified the Rome Statute on 23 March 2010. It is possible that in the future the Rome Statute will allow for prosecution of cases of enforced disappearance by the International Criminal Court (ICC). Bangladesh ratified the Rome Statute, which recognises the crime of enforced disappearance in its Article 7 (b). According to this, enforced disappearance is as an element of crimes against humanity, defined as acts ‘part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack’. Considering the level of impunity surrounding the crime of enforced disappearance in Bangladesh, with law enforcement agencies and judiciary becoming increasingly dysfunctional and inactive, an investigation from the ICC could put an end to impunity for the perpetrators of this crime. If this is not addressed and the cases continue to grow, the international community through the UN Security Council and in accordance with the UN Charter could consider intervening in line with the principle of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’. Based on this principle, the international community, through the UN, also has the responsibility to use appropriate means to help protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

Criminal law in Bangladesh has no provisions for the crime of enforced disappearance. However, there are penal provisions for crimes such as abduction, wrongful confinement, murder and grievous hurt. The Code of Criminal Procedure lays down all the paths to be taken to ensure a proper investigation and prosecution. However, according to the Code of Criminal Procedure, a Government sanction is required prior to suing a public servant or government official. This is difficult to obtain. As a result, it is difficult to hold members of law enforcement agencies or security forces accountable for crimes amounting to enforced disappearance.

The most concerning issue is that the Government is denying the existence and continuation of enforced disappearance in the country. Family members of victims have lodged several complaints, yet not received any efficient answer by authorities who are failing to investigate the incidents in a prompt manner.[12] To date, 97 countries have signed the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance but Bangladesh has not yet signed or ratified it.

Most of the time, the victims or their families file cases against unknown miscreants at the police stations. In reality no law enforcer will see charges brought against them. However, to seek legal proceedings, family members of the victim need to file a habeas corpus writ with the High Court under Article 102(2)[13] of the Bangladesh Constitution. In most cases, the family members of the disappeared victims cannot file writ petitions in the High Court Division of the Supreme Court due to financial constraints, threats from perpetrators, or fear of not getting back their dear ones, if they proceed further. The families of the disappeared go through a psychological trauma. It leaves the victims’ families in limbo, as they await the return of their dear ones.

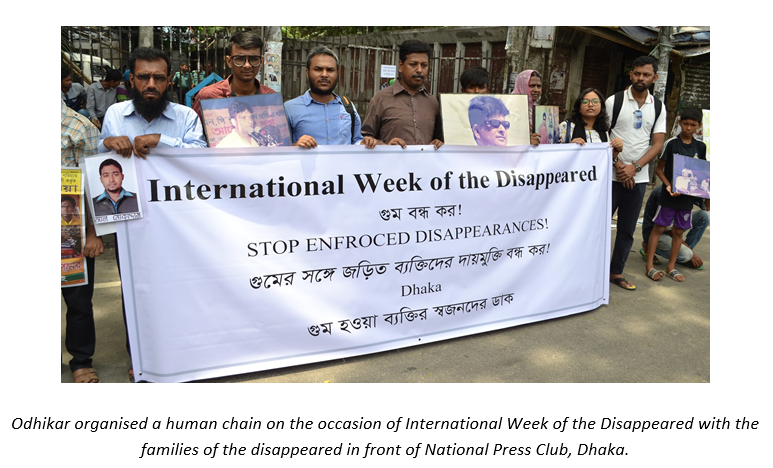

Therefore, to combat this heinous crime, Odhikar has advocated through campaigns and lobbying for Bangladesh to accede to the ICPPED and to adopt an Anti-Disappearance Law in Bangladesh. Odhikar has also put efforts in disseminating information on enforced disappearance in the country. It commemorated the International Week and International Day of the Disappeared, communicated with the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (UNWGEID), and set up a campaign for the criminalisation of enforced disappearance, among others.

Odhikar gathers information on enforced disappearances through its countrywide network of local human rights defenders, regularly documenting the cases of enforced disappearances through its documentation team and by updating its database. Odhikar includes such information in its monthly human rights monitoring reports, which are disseminated to the media and national and international networks.

Odhikar observes the International Week and International Day of the Disappeared with the families of the disappeared persons and human rights defenders. On these occasions, Odhikar organises a series of public events, including rallies, press conferences, human chains, and meetings in different locations in Bangladesh. Odhikar also issues joint statements with international human rights organisations. Odhikar submitted several cases to the UNWGEID using its standard communication form, requesting the UNWGEID to consider actions under the Urgent Appeal and Urgent Action procedures. The Working Group has acknowledged the receipt of the cases and transmitted some cases to the Government of Bangladesh.

Odhikar is trying to raise awareness about crimes of enforced disappearance in Asia through ongoing campaigns at the national, regional, and international levels, together with the families of the disappeared and civil society organisations. Furthermore, Odhikar has now approximately 400 trained active human rights defenders at the local level, many of whom are working with Odhikar from their own localities. They are involved in gathering information on human rights violations, campaign and lobbying activities of Odhikar. They are also strengthening the network of local human rights defenders and families of the disappeared.

Despite facing significant obstacles, Odhikar has been successful in making some impacts regarding the situation of enforced disappearance in Bangladesh. This has been possible mainly due to the continuous hard work of the organisation. Through its advocacy strategies, Odhikar highlighted issues related to enforced disappearance, creating a political consensus against this crime. People have become more concerned about the consequences of enforced disappearances, and this is exemplified by the creation of a network of families of the victims, which aims to inspire a social movement against enforced disappearances. The international community, organisations, and civil society reacted to the situation and urged the Government to stop enforced disappearance and sign the ICPPED.

Though the increased awareness about this crime among a large number of people, and the strengthened network of human rights defenders and victims’ families are important achievements, the most important and significant outcome is the creation of a network of the families of the disappeared. Through this network, they can raise their voices jointly, try to make the authorities accountable, and push them to take effective steps in this regard.

Because of their involvement in campaigns against enforced disappearances and speaking out in public, the families of the victims are often threatened by the members of law enforcement agencies. They are living in constant insecurity and fear. Human rights defenders who organised awareness programmes and campaigned against enforced disappearances have been put under surveillance by the intelligence agencies.

Odhikar commemorated the International Day of the Disappeared on 30 August 2014. To mark this international day and express solidarity with victims of enforced disappearances, Odhikar organised rallies and human chains in Rajshahi, Khulna, Chittagong, and Sylhet. Under this programme, at around 10:30 am, local human rights defenders associated with Odhikar initiated a rally from Sonadighi Mor in Rajshahi and formed a human chain in front of the press club. Moin Uddin, a focal person of Odhikar at Rajshahi coordinated the programme. After completion of the programme, at around 5:30 pm, some officials from Rajshahi Metropolitan City Detective Branch (DB) of Police led by Sub Inspector (SI) Mahabub visited the Amar Desh Rajshahi Bureau office where Moin Uddin works. At that time Moin Uddin was not in the office. The DB police called his cell phone and asked him to meet them at the office of the DB police by before midnight. They wanted to know about the programme on enforced disappearance and also about activities of Odhikar. DB police called Moin Uddin several times that night and asked him to provide a list of human rights defenders who were associated with Odhikar. The police also put pressure on him. On 31 August 2014 SI Mahabub and constable Mannan visited his office again to see the banners and placards and wrote down the headlines and slogans of the banner and placards. DB police told Moin Uddin that he had to get permission from local authority to organise such events in the future.

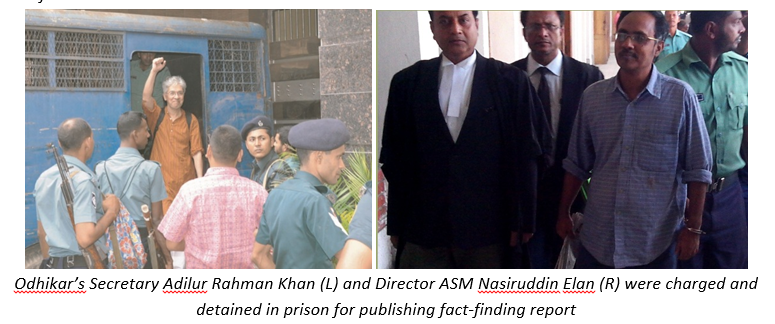

The Government continues to harass Odhikar for being vocal against human rights violations and for campaigning to stop them. Its Secretary Adilur Rahman Khan and Director ASM Nasiruddin Elan were charged and detained in prison for 62 and 25 days in prison respectively for publishing a fact-finding report. Human rights defenders who are working fearlessly to gather information and carry out their profession impartially are harassed and victimised. Furthermore, the NGO Affairs Bureau (NGOAB) has, for more than three years, barred the release of all project-related funds of Odhikar, and withheld the renewal of its registration in order to stop its human rights activities.

Despite facing persecution from the Government, Odhikar has continued to carry out human rights activities. Due to the hard and fearless work of its staff and human rights defenders and their dedication to human rights activism, Odhikar has improved its database on enforced disappearances.

The Government of Bangladesh must treat enforced disappearances as a criminal offence and sanction the offenders through a dedicated law. The Government has to investigate and explain all incidents of enforced disappearances and post-disappearance killings, allegedly perpetrated by law enforcement agencies. All victims of enforced disappearances should be returned to their families. The Government must bring the members of the security and law enforcement agencies who are involved in this crime to justice. Odhikar urges the Government to sign and ratify the ICPPED, adopted by the UN General Assembly.

***

For a PDF version of this case study, click here.

***

Footnotes

[1] http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CED/Pages/ConventionCED.aspx

[2] In 1994, a group of human rights activists initiated discussions and underscored the need to uphold the civil and political rights of the people of Bangladesh along with social, cultural and economic rights. Eventually, a decision was arrived at to form an organisation in order to advance such rights. On October 10, 1994, Odhikar (a Bangla word that means ‘rights’) came into being with the aim to create a wider monitoring and awareness raising system on the abuse of civil and political rights. The principal objectives of the organisation are to raise the awareness of human rights and its various abuses, on the one hand and to create a vibrant democratic system through election monitoring on the other. The organisation also performs policy advocacy to address the current human rights situation. Odhikar has no field or branch offices. Instead, it has trained more than 500 people all over the country to be human rights defenders, who are relied upon for information outside Dhaka. These activities help contribute to eventual positive steps towards the creation of transparency and accountability in the responsible sectors of the government with an aim to improve its human rights record and to facilitate an active democracy with the participation of people from all sections of society.

[3] Odhikar collects information about enforced disappearance through fact finding and also from different national print and electronic media. According to Odhikar’s documentation, from 2009-2017, 121 persons were disappeared who were directly involved with opposition political parties. Many national and international newspapers also published some news that the opposition political parties leaders and activists were disappeared because of their political identity. Please see- http://newagebd.net/71268/picked-up-a-year-ago-theyre-yet-to-return/#sthash.aKLZwvVC.dpbs

[4] According to Odhikar’s documentation, 54 persons were disappeared and later found dead from 2009-2017. See also- Arrested Jubo Dal leader killed in ‘gunfight’, Dhaka Tribune, 24 August 2017, http://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/nation/2017/08/24/arrested-jubo-dal-leader-killed-gunfight/

[5] Many incidents of enforced disappearance took place during the Liberation War in 1971, which continued after the war. Many notable intellectuals were abducted and their whereabouts remained unknown till their bodies were found. Thereafter such incidents occurred under various regimes. Among the disappeared persons, after the liberation war, were prominent film maker Zahir Raihan and an ethnic minority community leader Kalpana Chakma, who was disappeared in 1996.

[6] Odhikar’s documentation from 2009-2017. Please see- http://odhikar.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Statistics_Disappearance_2009-2017.pdf

[7] Article 9: Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention. No one shall be deprived of his liberty except on such grounds and in accordance with such procedure as are established by law.

[8] Article 16: Everyone shall have the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.

[9] Article 31: To enjoy the protection of the law, and to be treated in accordance with law, and only in accordance with law, is the inalienable right of every citizen, wherever he may be, and of every other person for the time being within Bangladesh, and in particular no action detrimental to the life, liberty, body, reputation or property of any person shall be taken except in accordance with law.

[10] Article 32: No person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty save in accordance with law.

[11] Article 7(2)(i) stated that “Enforced disappearance of persons” means the arrest, detention or abduction of persons by, or with the authorization, support or acquiescence of, a State or a political organization, followed by a refusal to acknowledge that deprivation of freedom or to give information on the fate or whereabouts of those persons, with the intention of removing them from the protection of the law for a prolonged period of time.

[12] BANGLADESH: Families demand return of their disappeared dear-ones within the month of Ramadan, Report published on 27 May 2016, http://odhikar.org/bangladesh-families-demand-return-of-their-disappeared-dear-ones-within-the-month-of-ramadan/

[13] Article 102(2): The High Court Division may, if satisfied that no other equally efficacious remedy is provided by law – (b) on the application of any person, make an order – (i) directing that a person in custody be brought before it so that it may satisfy itself that he is not being held in custody without lawful authority or in an unlawful manner[…]”