The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) welcomes the Indonesian Constitutional Court’s landmark decision declaring several articles that criminalise hoax and defamation to be unconstitutional and no longer have a binding force.

The judicial review was jointly submitted by human rights defenders Fatia Maulidiyanti and Haris Azhar, the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) Indonesia, and the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI), a FORUM-ASIA member organisation.

The Court specifically held that Articles 14 and 15 under Law 1/1946 on Criminal Law Regulations and Article 310 (1) of the Criminal Code are unconstitutional and considered to be rubber articles due to lack of specific standards and limitations, subjecting them to multiple interpretations which may cause legal uncertainty. Articles 14 and 15 criminalise the broadcast and dissemination of false information that are deemed to cause public disorder or unrest. Punishment may extend up to a 10-year imprisonment. Meanwhile, Article 310 criminalises defamation, with an imprisonment lasting up to 1 year and 4 months.

Remaining legal battle

The Court, however, dismissed the review of Articles 27 (3) and 45(3) under the previous Electronic Information and Transactions Law (EIT) Law–which criminalises online defamation–due to its amendment in 2024 which rendered it obsolete. Imprisonment under the law was prescribed to be up to 4 years.

Despite the Court’s decision, criminalisation against hoax and defamation remains intact under the amended Criminal Code and EIT law, signalling an ongoing battle against repressive legislation.

The old Criminal Code which regulates Articles 14 and 15 on hoax causing public disorder has been amended and it will be enforceable in 2026. However, the new Criminal Code still retains the hoax articles under Articles 263 and 264.

Defamation under Article 310 in the old Criminal Code is also present in the new Criminal Code under Article 433. Likewise, defamation under Articles 27(3) and 45(3) in the old EIT Law is also present in the newly amended EIT Law under Article 27(A) and 45 (4)

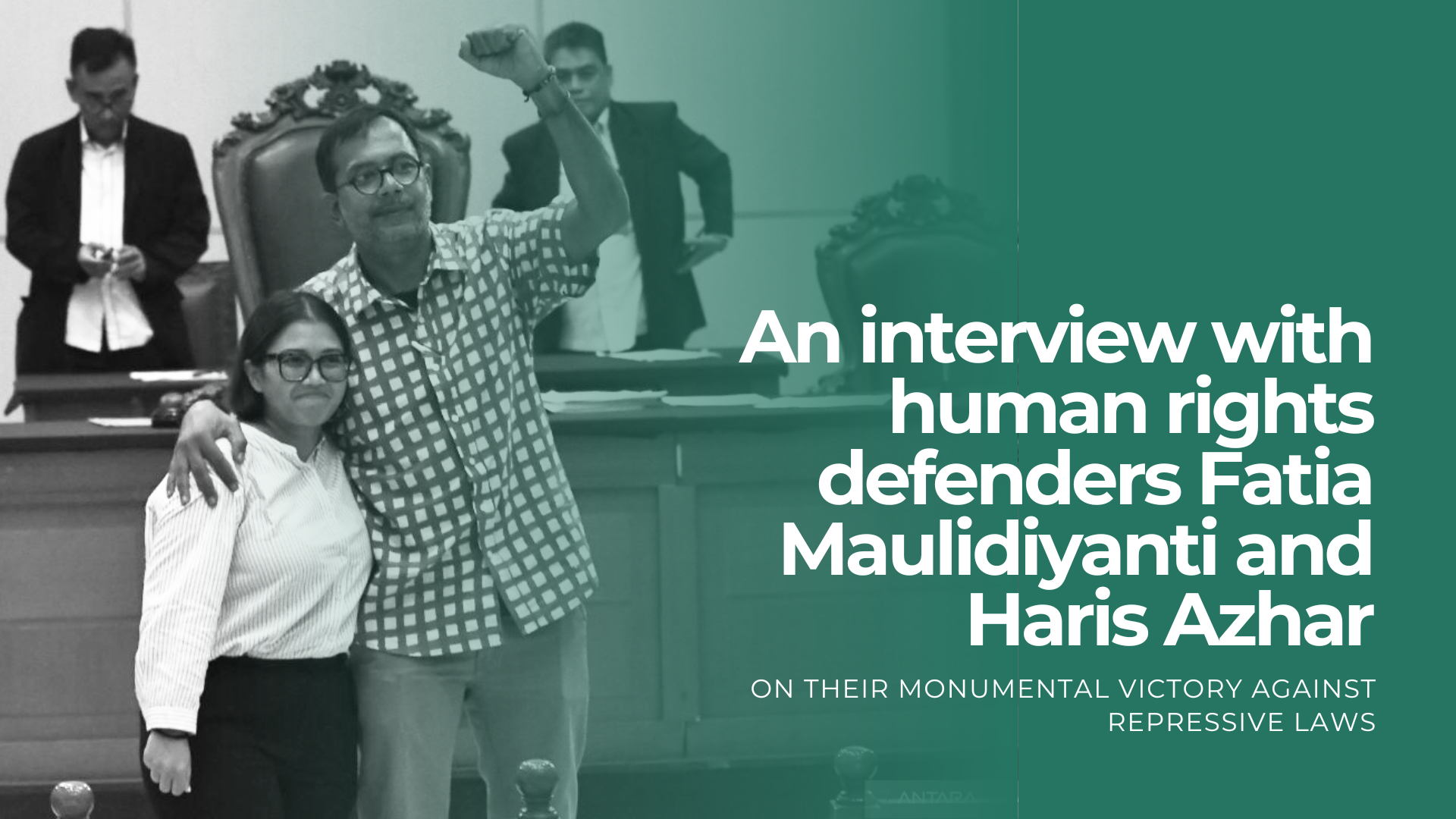

Interview with Fatia and Haris

FORUM-ASIA spoke with Fatia and Haris regarding their thoughts on how far defenders have come in their fight against repressive Indonesian laws. The duo spearheaded the judicial review process against the articles in question. For their human rights work, the pair was charged–under Articles 14 and 15 under Law 1/1946 on Criminal Law Regulations, Article 310 (1) of the Criminal Code and Articles 27 (3) and 45(3) of the EIT Law–but later on acquitted.

Q: What prompted you to file for this judicial review? Why is this important?

Fatia: Since the beginning, we may know from our monitoring data that the cases of criminalisation using the related articles such as the Electronic Information and Transaction (EIT) Law, hoax in the Criminal Code, and the Public Disorder Article are massive.

Some of the punishments using these articles are severe. This causes a chilling effect on the public, preventing them from enjoying their freedom of expression, particularly the journalists, activists, and academics that are very vulnerable to being criminalised by these articles.

However, even though it has been a long time, none of the public or non-governmental stakeholders has initiated to conduct the judicial review to the Constitutional Court. Therefore, we think that this is an important effort to try and to challenge the Constitutional Court regarding their views on human rights standards in implementing these articles.

Haris: There were two things to be implemented before we started the application of the Constitutional Court. We tried to stop the criminal charge which used ‘the anti human rights article’ against me and Fatia. Thus, we need to ask the Constitutional Court whether these articles are constitutional or not.

And we were struck when we found out that the article criminalises hoax. Articles 14 and 15 have never been challenged in the Constitutional Court, while we saw in the country hundreds of people being reported to the police and charged under these articles. So we were so motivated to challenge those articles at the Constitutional Court.

Q: How does the Court’s decision impact the state of freedom of expression in Indonesia? What is your hope? And what do you think comes next after this decision?

Fatia: We do hope that this achievement could bring direct impacts to the ongoing cases using the similar articles that are being challenged in the Judicial Review.

For instance, the case of criminalisation against three farmers in Pakel, Banyuwangi, and East Java who are currently facing five years of imprisonment through the Public Disorder Articles verdict by the Banyuwangi District Court. They are now in the process of appealing in the High Court. This should become a consideration by the panel of judges to release those farmers since the Article is no longer relevant.

Nonetheless, we do hope that the public could also be more brave to enjoy and practise their freedom of expression. And we also hope that this could be contagious to civil society to challenge such authoritarian articles at the Constitutional Court.

Because I think even though we already won the battle in the judicial process and won in getting some of the articles revoked, this also depends on the public’s willingness to practise their freedom of expression and to contribute to the democracy situation in Indonesia. Second, the considerations raised by the panel of judges in the Constitutional Court should become a reference for the judges that are facing similar cases on the ground as a principle of prudence in deciding a verdict under those articles.

Haris: Positively. There are few cases in the police office which still use Articles 14 and 15 of Law No. 1 (1946) and Article 310 (1) of the Criminal Code. This should be stopped.

Furthermore, the Constitutional Court’s decision is an important step for legal interpretation especially to recognise the constitutionality of the speech and its limitations which comply with the international human rights standard. However, we still have some other legal constraints, the anti-hoax articles exist in the new Criminal Code which will be applicable in 2026. Also in the new Electronic Information and Transactions Law (EIT) Law which came into effect in January 2024. So this is a hide-and-seek play. We managed to fight against the Law 1/1946, but a similar threat appeared from the other loopholes.

Q: What can the international community–including fellow ASEAN countries–do to help with the situation?

Fatia: In my opinion, ASEAN is the only regional government-to-government organisation that has very weak standards on human rights and democracy implementations. They have their own standards in implementing human rights obligations and have similar patterns due to conflicts such as Myanmar, Papua, and other limitations to human rights defenders in various countries in ASEAN–not even touching the bare minimum of the international human rights standards.

However, with the common situations that the ASEAN’s people are facing right now, this should become a communal understanding and ammunition among the them to strengthen the solidarity and to establish a more concrete movement to demand justice from state leaders. Not only by a critical engagement through hearings with the ASEAN member states in ASEAN People’s Forum, but also in some kind of a strong movement that demands the reform of ASEAN mechanism on human rights–demanding it to tackle the injustice, democracy situation, and human rights in ASEAN.

Haris: As always, the practice and quality of the ASEAN government are similar, bad and low for human rights and democracy. So it is important to establish more and more awareness among people regarding the threat, practice, and regulation from the anti-speech government within the ASEAN countries. At the same time, strengthening the people – oriented linkage to maintain the advocacy on several issues such as anti-fraud, protection of human rights, safe and green environment, and accountability of the business sector. This is very classic, but the consistency to do the classic is the precious strategy to tackle the oligarch who used the anti-speech article to diminish dissent.

Q: What is your message to the Government of Indonesia in this regard?

Fatia: There are too many messages that we already delivered and want to deliver. However, with this current situation in Indonesia–particularly post-election and with the various acts that have been done by the President ridiculously being ignored–I am very pessimistic because the normalisation of the situation is very extreme.

This message is more for the public: that the public should use their rights to implement freedom of expression and to demand accountability for all of the recklessness being done by the current government.

Haris: Nothing, because it’s useless to message them at this moment.

Q: What is your message for other human rights defenders in Indonesia and Asia who are continuously challenging repressive laws despite the personal risks to their safety?

Fatia: Human rights defenders, CSOs like KontraS will probably always be a pebble for naughty elites and rulers who are easily offended. But it is precisely because we exist that Indonesia today can still be proud of being a democratic country with respect for human rights. KontraS and civil society organisations in the field of human rights need to be supported through state openness.

Working in the human rights sector is easier said than done. The involvement of women in the human rights movement is very important because women are often underestimated and considered a vulnerable group due to layers of threats. Threats that continue to be used to spread fear in the women human rights defenders’ movement. The decision to become a woman human rights defender is not only by choice but also by belief. It is not a single-handed work that we can do alone, the more problems we find in human rights implementations, there should be more movements, more people eager to become women/human rights defenders, particularly the young generations.

Young generations should have more space, more bravery, and more critical thinking to continue the chain of struggle in human rights movements.

Haris: Speech and expression are few among other needs for every citizen to take part in (local) public policy complaining or democratisation. It is a shame if we stand as rights advocates, academicians, or influential figures but have no practice, no courage, or the ability to speak or express ourselves in our advocacy while standing for the people’s rights. Meanwhile, the repressive law always appears or is even interpreted blatantly by the law enforcement officer.

In short, I would say we have to realise the two elements of advocacy in these coming years. Firstly, the substantive part and secondly, the advocacy against the attack or the barriers to our advocacy. These two things should not always be mixed in the same organisation, the same group at the same issues. I witnessed this situation. I feel sorry that the group has to share their time and energy from the same program, to handle the attack on the street, to argue in UN forums, and to appear in the court session. There shall be a professional distinguished part of advocacy in the future. Let’s say, labour of division, to avoid the burnout of civil society.

Q: What is next for Fatia and Haris?

Fatia: I will continue my work in human rights issues–as a researcher, campaigner, and also teacher of younger generations–to raise their awareness in human rights movements. I also plan to continue my postgraduate study to raise my capability in my human rights works.

Haris: For me, I will keep practising law and advocacy for vulnerable groups and teaching human rights for the youngsters.