I. Context

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) commits itself to the achievement of a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, as it remains to be a major source of development finance in the region. However, five decades of its operations in the region have often led to negative development outcomes, as developing countries are buried deeper in debt, neoliberal policies have exacerbated inequalities, basic services and goods are privatized, marginalized sectors are victimized by development aggression, and profit-oriented development and climate initiatives are pursued despite their adverse impacts on people and the environment.

Given that the ADB is a channel for Official Development Assistance (ODA) or aid, the bank has the responsibility to uphold human rights, preserve the ecological balance, and forward sustainable, inclusive development. Furthermore, the ADB should be accountable to the people, who are supposedly partners and beneficiaries of their initiatives. The ADB as a critical and influential development institution in the region should be held to the highest standard in order to ensure that the bank contributes positively to development and pursues solutions to address the multiple and mutually reinforcing economic, social, political, and climate crises.

A step towards this is the update of its Safeguard Policy Statement of 2009, as the ADB recently released the Environmental and Social Framework (ESF), which details the “mandatory performance standards” it upholds in planning, designing and implementing development projects. The ESF’s main objective is to promote the sustainability of project outcomes by protecting the environment and the people from potential adverse impacts. Given the historic impact of the bank on the people and the environment, the update of its safeguards is critical and urgent, especially for communities most affected by their projects and policies. CSOs have been active in participating in the bank’s Safeguard Policy Review process and have forwarded key demands in consultations and during this year’s Annual Meeting. However, the draft ESF has not incorporated key recommendations and lacks the strong language on human rights, accountability, and environmental standards.

In this manner, CSOs continue to forward principles and recommendations to be reflected in the ESF to effectively avoid, minimize, address and remedy risks and negative impacts of its projects and operations. The framework should demonstrate ADB’s commitment to contributing to development, upholding human rights and protecting the environment. At the core of this commitment is ensuring remedy, repair and justice for communities and sectors at the receiving end of the bank’s operations. This also entails promoting inclusive and meaningful processes, recognizing the people as actors and partners in development. Furthermore, the ESF should enact standards that advance a people-centered, rights-based and climate-resilient development for the region. The real measure of the ESF’s success lies in how marginalized communities are able to chart their own development paths, to assert their rights, and to hold the bank accountable for any adverse impacts they have created and can cause.

II. Statement of Principles and Recommendations

We, as members of the civil society, believe that these principles and recommendations must be reflected in ADB’s Environmental and Social Framework:

1) Adopt the “do no harm” principle and a rights-based, people-centered framework. Following the “do no harm” principle, ADB’s ESF must be able to effectively prevent, reduce, and control potential risks and adverse impacts from its financing and support towards technical assistance, infrastructure projects, development and climate initiatives. Negative impacts to people’s homes, livelihoods, culture, and ways of life must be avoided at all costs. Projects financed by the bank that neither contribute towards mitigating environmental and climate challenges, nor aid in facilitating achievement of people’s development priorities, effective climate action, and the sustainable development goals (SDGs), must not be pursued. The bank must abandon projects and policies that have proven to or will potentially harm peoples’ sovereignty, economy, peace and security. The updated ESF must explicitly adopt a rights-based and people-centered framework. As it modernizes its safeguards, the ADB must uphold the primacy of human rights over its policies and operations.

Specific recommendations:

- Explicitly adopt international human rights norms and standards. The ADB must also align their operations with the UN Declaration of Human Rights and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Human rights should not be compromised for the sake of development initiatives. A human rights due diligence assessment must be a requirement for all projects, despite its scale and scope. The bank and its partners must allow for an external review process to take place, which assesses their compliance with human rights norms and standards in ADB’s operations. This process will be led by impacted communities, with the participation of other stakeholders and development actors, and will measure ADB’s commitment to human rights.

- The ESF should be able to recognize and address the needs of marginalized sectors. Upholding people’s right to development, the needs of marginalized populations, such as women and children, peasants, fisherfolk, workers, urban poor, coastal communities, Indigenous Peoples, pastoral communities, nomadic peoples, disenfranchised castes, stateless, religious and ethnic minorities, among others, should be adequately met. A stronger language on the adoption of gender-responsive frameworks is needed. For workers it employs and affects, the bank must guarantee safe and humane working conditions. This can be ensured by upholding international labor standards and ensuring occupational health and safety measures. The ESS7 on Indigenous Peoples must strictly comply with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UN DRIP). Projects must only be implemented with the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of affected indigenous communities, with the ADB having a clear process and definite criteria on how to secure FPIC. The FPIC process should be culturally-appropriate, inclusive, transparent, and ultimately uphold Indigenous Peoples’ rights over their ancestral lands, traditional knowledge and culture, and overall development.

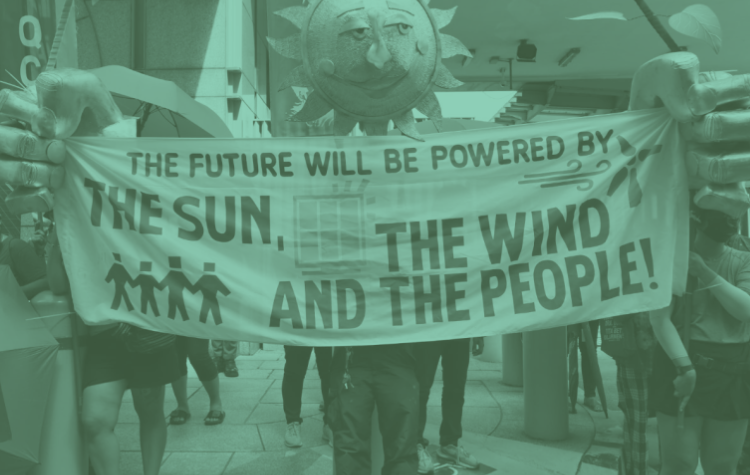

2) As the region’s ‘climate bank’, the ADB’s ESF should embark on a real zero pathway, a just and equitable transition, and a climate-resilient future for all. In order to genuinely address the impacts of climate change, the bank must decarbonize its operations and portfolio aligned with a real zero pathway. This includes not only decommissioning and halting financing towards fossil fuel and non-renewable power plants, but also supporting sustainable means of producing clean, renewable energy. In contributing to the transition to renewable energy systems, the ADB should pursue energy projects that are democratically-owned, accessible, and affordable. Financing should not be channeled to false and market-based solutions like carbon offsets, carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS), Waste-to-Energy (WTE) incinerators, megadams, and geothermal plants.

Specific recommendations:

- Align all operations with the Paris Agreement and conduct its due diligence to prevent further harm from climate change. To ensure that initiatives uphold environmental sustainability, the ESF should strictly adhere to the Paris Agreement, an international treaty requiring economic and social transformation to combat the climate emergency. Operations should be aligned with the 1.5 degrees Celsius goal or even more ambitious climate goals, compatible with reaching a global CO2 emissions decline, and not reliant on false or unproven solutions. The bank should end all direct and indirect financing for fossil fuels, aiming for real zero emissions. To forward transparency and accountability, the ESF should also require the bank and its partners to annually quantify and report the carbon footprint of its portfolio, including indirect contributions to carbon emissions.

- Contribute to a just and equitable energy transition. Especially in implementing energy, transport, extractive industries and infrastructure initiatives, these should not perpetuate or worsen threats faced by frontline communities from climate change. The energy transition must be consistent with evidence-based standards, not subject to market-based solutions and the privatization of energy services. These initiatives should contribute in eradicating energy poverty and democratizing ownership over energy resources and systems. A just and equitable transition to renewable energy systems puts human rights, justice, and peoples at its center. Energy projects must address the needs of affected communities and sectors, especially formal and informal workers, farmers, fisherfolk, Indigenous Peoples, women and children. This must include upholding labor and human rights standards, ensuring affected peoples are included in processes, cushioning socioeconomic impacts on the marginalized, and providing equitable benefits for communities.

- Environmental and Social Assessments should be thoroughly conducted with various stakeholders, with a principal role towards affected communities, for all projects despite its size and scope, and conducted prior financing approvals. These assessments must be conducted in an independent and inclusive manner, with various stakeholders, especially communities, sectors, and civil society, participating in the process. Comprehensive information regarding the bank’s projects and policies must be made publicly available in a timely manner. The assessment should be accompanied with a comprehensive mitigation plan and course of action for communities and sectors that will have their lives, homes, livelihoods, culture, and environment impacted by the project. Adoption of a mitigation hierarchy requires that prior to approval of project financing, the ADB ensures measures are adopted that avoid and minimize environmental and social impacts as far as economically and technically feasible. Plans to avoid, mitigate and address risks should be formulated with and agreed upon by those going to be impacted by the project.

3) While remaining robust and comprehensive, the ESF must be responsive and anticipatory in order to effectively reduce risks for marginalized sectors and communities in developing member countries. The ESF recognizes the need for a “differentiated approach” given the diversity of contexts in the Asia-Pacific region. Despite the need for a contextual implementation of the ESF, the bank must have minimum standards in order to address the threats and risks its projects can bring to member countries. The ESF should be forward-looking, anticipating emerging risks and threats given the increase in conflict, intersecting development and climate challenges, changing development landscape, and technological innovation. The bank must be flexible in responding to emerging crises and the needs of the people on the ground, especially in the case of withdrawing investments to authoritarian governments or providing immediate assistance to vulnerable populations.

Specific recommendations:

- Detail standards and roles for Country Safeguard Systems (CSS) in the new ESF. In the current draft, there is no mention of the CSS in the ESF and it still remains unclear as to how these are going to figure in the new policy. If the ADB will continue to use the CSS, the bank must assess countries’ capacities and contexts to effectively mitigate threats and risks. The framework should include minimum standards for CSS, providing adequate support and training to partner countries to capacitate systems and staff for proper implementation of safeguards. Strengthening CSS must not lead to further liberalization of policies that weaken states’ capacity to regulate the private sector, but must allow for the promotion of human rights, rightful participation of CSOs in development processes and accountability of development actors.

- Security assessment and management for ADB projects should take into consideration different country and local contexts, in order to effectively protect affected peoples. Upholding people’s rights, safety and security should be of utmost importance. Various communities have highlighted how state and private armed forces have been used to forcibly displace them from their homes, violently stop demonstrations, and directly attack them for opposing these projects. In making considerations for people’s security, inclusion of affected peoples and communities is crucial in order to arrive at an arrangement that can provide protection.

- The ESF should have specific provisions for its operations in fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCAS). Acknowledging that risks and adverse impacts multiply in such contexts, the ADB has to set-up processes and mechanisms to immediately mitigate risks and mobilize assistance for immediate humanitarian needs. Adopting the Triple Nexus framework, initiatives in FCAS must work towards integrating humanitarian, development and peace efforts with other development actors. Furthermore, ADB’s assistance in FCAS must contribute in addressing the root causes of conflict and pursuing long-standing development and peace.

- With the increased use of technology and digitalization in its development initiatives, the ADB should adopt standards in safeguarding people’s rights, data, and privacy. In pursuing digital solutions, the bank should ensure that these are based on sound risk and impact assessments that entail inclusive, meaningful, and participatory consultations with recipient governments, civil society, and affected communities and sectors. The ADB should contribute to a digital transformation that can adequately improve delivery of assistance and address the digital divide that disproportionately impacts women, Indigenous Peoples, and rural communities. The ESF should include provisions on data justice to uphold peoples’ collective rights over data and promotion of democratically-owned digital infrastructure and technologies.

4) Ensure transparency and accountability of the bank and its partners, including national and local governments, private sector entities, financial intermediaries, and ensure all entities adhere to the ESF. For the ADB to exhibit its commitment in pursuing a prosperous, inclusive, resilient and sustainable Asia-Pacific, it must ensure that its safeguards are implemented across financing modalities and member countries, as it exercises significant oversight and accountability over its partners’ activities. Ultimately, development projects should not serve private sector or corporate interests, but the actual needs of vulnerable and marginalized populations.

Specific recommendations:

- The ESF should include specific standards for various financing modalities and private sector partners to ensure proper regulation and oversight. As the bank continues to partner with various private sector entities in its operations, proper regulatory mechanisms must be enacted by the ADB and governments over their business operations. Private sector entities must remain accountable in following the country’s laws and policies, and in upholding human rights. Multinational corporations that have questionable human rights records must not be considered as partners by the bank, and should not conduct activities in developing member countries. The ADB should always assume responsibility and accountability over co-financed and financial intermediary projects, and not leave the implementation of safeguards to its partners. The bank should also ensure that its own and partners’ operations are aligned with international human rights guidelines and regulations, the Kampala Principles for Effective Private Sector Engagement, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) core labor standards, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, the OECD Guidelines on Due Diligence, and other such agreements.

- The ESF should have a standalone standard for financial intermediaries (FIs), given the high-risk nature of their operations and processes. This will entail the ADB to be more proactive in monitoring FIs’ compliance with the bank’s standards and policies. This standard should be able to categorize projects properly according to risk and ensure that the bank’s safeguards will be reflected in all FI projects, even with their own partners and contractors. Financial intermediaries must also be required to be transparent and properly disclose information. Projects that have a higher risk should be monitored more intensely by the bank, including by site visits which can often be the only way to reach project-affected communities. ADB mechanisms for remedy and redress should also be applicable to FI projects.

- Improve the bank’s policies on information disclosure. Project information, assessments and management plans must be made available to affected communities and sectors to facilitate meaningful involvement. The name, sector and location of higher risk FI sub-projects should be disclosed on the ADB’s website before approval to enable scrutiny. The information should be accessible online and offline, translated to local languages, easily understood and provided in a timely manner. Outcomes of consultations must also be published publicly.

- Undertake a comprehensive review and update of the bank’s Accountability Mechanism. This review should be conducted independently, transparently, and in an inclusive and meaningful manner. The mechanism should be able to exact accountability from the bank and its government and private sector partners. In the new accountability mechanism, good faith efforts should be abandoned as it puts the burden of proof on victims and contributes to a delay in justice.

5) Stakeholder engagement under the ESF must award a principal role to affected communities and sectors, civil society organizations, people’s organizations and community-based organizations. In pursuing inclusive partnerships especially with affected communities and sectors, there is a need to provide an enabling environment for civil society. This would entail recognizing the role of civil society as development actors in their own right, involving them in relevant processes, and upholding their monitoring role. The reversal of shrinking civic spaces in the region will protect civil society organizations, human rights activists, environmental defenders and affected communities, as well as contribute to positive development outcomes.

Specific recommendations:

- Affected communities and sectors, as well as civil society organizations, community-based organizations and people’s organizations, should be meaningfully involved from the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the project. The bank’s processes should be inclusive and participatory, especially to the vulnerable and marginalized populations. Affected communities should have a principal role in the identification, design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of development projects. Consultation and planning of projects must include the voices of vulnerable communities, such as Indigenous Peoples, farmers, fisherfolk, workers, rural women and children, and urban poor, as they are the most impacted by these projects.

- Adopt more stringent standards for cases of reprisal and retaliation to address hindrances to civil society and communities’ participation. The ADB should adopt a zero tolerance policy towards reprisals, country and project-specific retaliation risk assessments, and reprisal-sensitive engagement with affected communities and CSOs. In contexts where there are heightened risks of reprisals, such as fragile and conflict-affected states, the bank must be able to properly assess and implement measures for preventing and addressing these threats. In tackling reprisals, the bank should not depend on private sector partners and governments to address, mitigate, and prevent reprisal risks. Instead, the bank should lead and conduct its own participatory, independent, ongoing, transparent, and accountable assessments. The ADB should also be proactive in addressing cases of retaliation, by establishing a reprisal response protocol, conducting in-depth investigations, providing appropriate remedy, and building capacities and leverage to adequately respond to these risks. In designing and implementing mitigation measures and responses for reprisals, the bank should meaningfully involve members of civil society, especially marginalized communities and sectors, community-based organizations, CSOs, human rights and environmental defenders.

6) The ESF should forward a just approach to development as it provides repair and remedy to victims of its harmful projects and policies. Decades of the bank’s operations in the region have proven to be harmful to marginalized communities and sectors as they face the adverse impacts of development projects. The previous iterations of its Safeguard Policy have left gaps that allow for human rights violations, forced displacement, encroachment on ancestral land, threats to people’s security, and environmental destruction. To provide protection to affected peoples, the bank should have mechanisms and processes that can receive grievances and complaints, and work towards arriving at adequate solutions to avoid and minimize risk.

Specific recommendations:

- The ESF must take responsibility for its adverse impacts from its projects and policies under its previous SPS. Acknowledging that the previous Safeguard Policy Statement had gaps, the bank must be held accountable for the violation of people’s rights and negative impacts on their lives, livelihood and environment, brought about by their operations. Proper redress and reparations to the affected peoples should be pursued, which is only possible by listening to the voices and calls of these communities and sectors.

- The bank’s grievance redress mechanisms (GRMs) should be made available to affected peoples and follow the UNGPs’ Effectiveness Criteria. Grievance redress mechanisms must be made available to affected communities and sectors, both at the project level and through an institution-wide redressal mechanism of the ADB. The bank should set-up legitimate, accessible, predictable, equitable, transparent, gender-responsive, and rights-compatible grievance mechanisms. Furthermore, marginalized populations should be involved in the design, implementation and monitoring of such mechanisms. Complaints and grievances should be adequately addressed by the ADB by providing plans to investigate and remedy violations.

- Other than GRMs, the bank should support affected peoples’ access to justice. Affected peoples should be able to choose which processes, mechanisms, policies and institutions to use when bringing their concerns and demands forward. The bank should be able to engage, provide needed information and support in these other channels of remedy and justice in order to uphold peoples’ rights.

7) The ADB and its ESF should demonstrate its commitment to the effective development cooperation principles of democratic country ownership, focus on results, inclusive partnerships, and mutual transparency and accountability. Development priorities determined by countries should reflect the needs of the people, and not the private sector nor the country elite. The bank’s projects should contribute towards eradicating poverty, reducing inequalities, upholding sustainable development, and addressing the climate emergency. The ADB’s processes must be inclusive and participatory, ensuring that the democratic rights of communities, peoples’ organizations and civil society organizations are upheld in the design, implementation, and monitoring of projects. Transparency in its investments and accountability in its project implementation are also demanded from the bank.

Download the critique here: ADB Draft ESF_ CSO Critique

Signatories:

- Accountability Counsel, Global

- ACTC CD, Mauritania

- Aid/Watch, Australia

- Alliance for Climate Justice and Clean Energy, Pakistan

- All Nepal Peasants Federation, Nepal

- Alternate Development Services, Pakistan

- Alternative Law Collective, Pakistan

- Asia Development Alliance, Regional

- Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development, Regional

- Association of Nepal Kirat Kulung Language and Culture Development, Nepal

- Association for Promotion Sustainable Development, India

- Aware Girls, Pakistan

- Bank Climate Advocates, United States

- Beyond Beijing Committee, Nepal

- Botswana Watch Organization, Botswana

- Center for Environment, Human Rights & Development Forum, Bangladesh

- Center for Good Governance and Peace, Nepal

- Center for Women & Children Solidarity Network, India

- Centre for Research and Advocacy Manipur, India

- Coastal Development Partnership, Bangladesh

- Community Empowerment and Social Justice Network, Nepal

- Community Initiatives for Development in Pakistan, Pakistan

- Community Resource Centre, Thailand

- Council for People’s Development and Governance, Philippines

- Civil Society Education Partnership, Timor-Leste

- DanChurchAid, Cambodia

- Dewan Adat Papua, West Papua Indonesia

- Dhewa, Pakistan

- Dialetika, Timor-Leste

- Disability Peoples Forum, Uganda

- Ekumenická Akademie, Czech Republic

- EquityBD, Bangladesh

- FIAN Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka

- Front Mahasiswa Nasional, Indonesia

- Gender Action, Global

- Green Advocates International, Liberia

- IBON International, Global

- Indigenous Women Legal Awareness Group, Nepal

- Indus Consortium, Pakistan

- Inisiasi Masyarakat Adat, Indonesia

- Institute for National and Democracy Studies, Indonesia

- International Indigenous Peoples Movement for Self-Determination and Liberation, Global

- Jalaur River for the People’s Movement, Philippines

- Krisoker Sor, Bangladesh

- Ladlad Caraga Inc., Philippines

- Mining Watch Canada, Canada

- Nash Vek Public Foundation, Kyrgyzstan

- National Campaign for Sustainable Development Nepal, Nepal

- NGO Forum on Cambodia, Cambodia

- North-East Affected Area Development Society, India

- Pacific Island Association for NGOs, Fiji

- Participatory Research and Action Network, Bangladesh

- Pasumai Thaayagam Foundation, India

- Peace Point Development Foundation, Nigeria

- Protection International, Belgium

- Psychological Responsiveness NGO, Mongolia

- Reality of Aid-Asia Pacific, Regional

- Right Energy Partnership with Indigenous Peoples, Malaysia

- Rural Area Development Programme, Nepal

- Rural Development Organization, Pakistan

- Sri Lanka Nature Group, Sri Lanka

- Support for Women in Agriculture and Environment, Uganda

- Swedwatch, Sweden

- Uganda Peace Foundation, Uganda

- Union des Amis Socio Culturels d’Action en Developpement, Haiti

- University of Dhaka, Bangladesh

- Youth Council in Action for Nation, Nepal